1 A - Introduction to the study of Phonetics and Phonology

Once we are introduced to the study of Phonetics and Phonology, we come across different concepts, theory and other matters that we should know. Thus, one of the main points the first chapter of the book by Peter Roach is concerned about is the reason why it is necessary to learn a theoretical context about Phonetics and Phonology. The answer that arises is that we do not simply need to know how phonemes work, are pronounced or such. As people who will work with the language we need to go deeper in the understanding of the mentioned theoretical context.1 A - Phonemes and other aspects of pronunciation

English spelling doesn't give us clear enough information as to how a word is pronounced. This is a notion Peter Roach is very aware of and suggests in his course that we should learn to think of English pronunciation in terms of phonemes rather than letters. When we learn and teach English, therefore, phonemes are a quite useful tool. Other important aspects of pronunciation are syllable, stress and intonation.

1 A - Accents and Dialects

Accent and dialect are often confused and mistakenly used interchangeably, but they refer to different things. The latter refers to a variety of a language which is different from another not only in pronunciation, but also in vocabulary, grammar and word-order. On the contrary, accent is only about differences in pronunciation.

1 B - Aspects of connected speech. Assimilation. Elision. Linking.

When we talk about connected speech we refer to the natural way native English speakers actually speak as opposed to a "mechanical way of speaking" which is orientated to how words are pronounced in isolation. Three of the aspects of connected speech are: assimilation, elision and linking.Assimilation: cases of assimilation are found when a sound (specially a consonant) in a word causes changes in sounds in neighbouring words. For example, when the sound /d/ is precedes a /j/ the latter will likely become /dz/. An instance of this can be appreciated in: "could you" (d causes y to sound /dz/). Another example is /t/ turning /j/ into /ch/. Example: 'don't you' becomes 'doncha.' It's worth noting that this phenomenon is likely to be found in rapid, casual speech rather than in slow, careful speech. Assimilation can be regressive (when a sound modifies a sound that is earlier in the utterance) or progressive (the modification of a sound that appears later in the utterance).

Elision: under certain circumstances sounds disappear. Some examples are:

- Loss of weak vowel after p, t, k. So 'today' becomes 't-day'

- Weak vowel + n, l, r becomes syllabic consonant. 'tonight' becomes 't-night' or 'remember' becomes 'r-member'

- Loss if final /v/ in 'of' before consonants: 'waste-o-money'

1 C - Long vowels, diphthongs & triphthongs

In English there are seven short vowels and five long vowels. The latter tend to be longer than the first, but the difference is not only length but also quality.

Graphically, the symbols for long vowels consist of one vowel symbol plus two dots, but as the difference between short and long vowels is not only length, it we omitted the two dots the vowel symbols would still be all different from each other. Therefore it's important to know that the length mark made of two dots is used not because it is essential but because it helps learners to remember the length difference.

mica diphthongs, triphthongs

2 A - The production of speech sounds. Articulators above the larynx

We have a large set of muscles that can produce changes in the shape of the vocal tract. The muscles in the chest produce the air flow that is needed for almost all speech sounds; the muscles in the larynx produce different modifications in the flow of air from the chest to the mouth. After passing through the larynx, the air goes through the vocal tract which ends at the mouth and nostrils.

There are seven articulators above the larynx, which are:

- The pharynx: It is a tube that begins above the larynx and whose top is divided in two parts. One part is the back of the mouth and the other is the way through the nasal cavity.

- The soft palate: It allows the air to pass through the nose or through the mouth. The sounds/k/, /g/ and /ŋ/ are made by making use of this articulator. They are called velar sounds.

- The hard palate: It is a curved surface in the upper part of the mouth.

- The alveolar ridge: It is a surface covered with little ridges situated between the teeth and the hard palate. There are sounds called alveolar which are made by the tongue touching this place, which are /t-d-n/.

- The tongue: It is the most important articulator because it can be moved to many different places. We divide the tongue into: tip, blade, front, center, back and root.

- The teeth: They are located immediately behind the lips. Sounds produced with the tongue touching the teeth are called "dental": /θ-ð/

- The lips: They are very important in speech. They can be pressed together as for /p-b/ or brought into contact with the teeth as for /f-v/ or rounded for vowels like /uː/. Sounds made with the lips pressed together are called "bilabial", and those with the lower lip making contact with the upper teeth are called "labio-dental".

2 A - Vowels and consonants. The cardinal vowel system

The most common distinction between vowels and consonants is made from the way they are produced, and therefore we can say that vowels are produced in such a way that there is no obstruction of the air coming from the lungs as it passes through the vocal tract. Consonants, on the other hand, are produced with the air undergoing different sorts of obstruction in its way through the vocal tract.

But as there are some cases of uncertainty, there is another way of distinguishing English sounds, which is by looking at the different contexts and positions in which particular sounds can occur. Studying sounds in this way has shown that there are two groups of sounds with quite different patterns of distribution and these two groups are those of vowels and consonants.

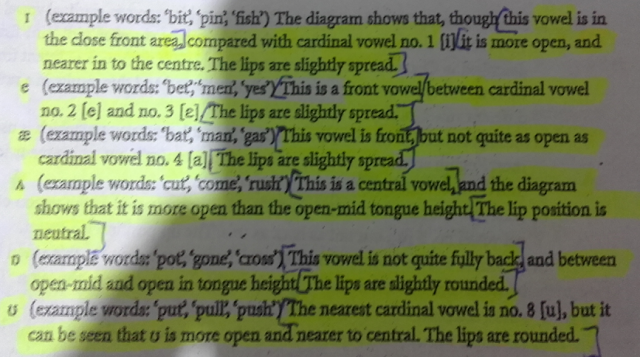

Once the distinction can be seen, it is necessary to know in what ways vowels differ from each others; thus, the first point to consider is the shape and position of the tongue by describing two things: first, the vertical distance between the tongue and the palate, and second, the part of the tongue which is raised highest. In other words, the tongue height, frontness and backness.

In addition, it is worth noting another point which rather than the differences between vowels, it has to do with quality. This is lip-rounding, and there are considered three shapes that the lips can take: rounded (as in "u"), spread (as in "i") and neutral (as in the sound people do when hesitating "er").

On a different note, cardinal vowels are vowels from no particular language. They are standard reference system that represents the range of vowels that the human apparatus can make. They are developed for the sake of classifying the vowels used in a particular language. They show extremes of vowel quality.

2 A - Manner and place of articulation

Consonants can be classified according to the place and manner of articulation. The place of articulation refers to where the organs meet to produce the different consonants. Under this criteria, the groups are:

- Bilabial: The upper and lower lip are pressed together. For example /p-b-m/

- Labio-dental: The lower lip touches the upper teeth. For example /f-v/

- Dental: The tongue is put between the teeth. For example /ð-θ/

- Alveolar: The tongue touches the alveolar ridge. For example /t-d-s-z-n-l/

- Palato-alveolar: The tip and blade of the tongue are put against the part where the alveolar ridge ends and the hard palate begins. For example /ʃ-ʒ-tʃ-dʒ/

- Velar: The back of the tongue touches the soft palate. For example /k-g-ŋ/

- Glottal: This sound is produced in the glottis which is the opening between the vocal cords. For example /h/

On the other hand, the manner of articulation is the way in which the stream of air is obstructed:

- Plosive: It is made with two movements. The first one is the closure part in which one or two articulators are moved together so that air cannot escape through the mouth. In the second movement, the air is allowed to escape, and such movement is called release. When the air is released we hear a noise called plosion. For example /p-b-t-d-k-g/

- Fricative: It is a sound in which the articulator is brought near the point of articulation and as there is no obstruction the air passes but with friction. For example /s-z-ʃ-ʒ/

- Affricative: It is a combination of a plosive + a fricative. For example /tʃ-dʒ/

- Nasal: It is a sound with no obstruction in the mouth because as the velum is lowered the air escapes through the nose. For example /m-n-ŋ/

- Lateral: The blade of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge so the air escapes through the sides of the tongue. For example /l/

- Approximant: The articulators are near each other, but when the air passes through them there is no friction. For example /j-w-l-r/

2 B - The phonetic value of "ed" suffixes

The "ed" suffix can occur in regular verbs and adjectives. Verbs in past simple or with its past participle are formed with "d" or "ed" added to its base. This ending is pronounced in one of three ways:

- If the "ed" is preceded by a voiceless sound like /p-k-f-θ-s-ʃ-tʃ/ it is pronounced /t/.

- If the "ed" is preceded by a voiced sound like /b-g-v-ð-l-m-n-ŋ-z-ʒ-dʒ/ a vowel, diphthong or triphthong, then the "ed" is pronounced /d/.

- If the "ed" is preceded by the sound of /t/ or /d/ it is pronounced /ɪd/

naked wicked

2 C - Short Vowels

3 A - The Larynx. The Vocal Folds.

The larynx's structure is made of two large hollow cartilages which are attached to the top of the trachea. This structure makes a shape of a box inside of which there are two thick flaps of muscle called vocal folds. At the back they are attached to a pair of small cartilages called arytinoid cartilages.

If these cartilages move, the vocal folds will move producing a very complex range of changes in their position that are important in speech. There are four easily recognizable states of the vocal folds:

• wide apart: It is the state in which the vocal folds are for common breathing and usually during voiceless consonants.

• narrow glottis: when the air passes through the glottis when it is narrowed the result is a fricative sound.

• position for vocal fold vibration: when the edges of the vocal folds are touching each other or nearly touching the air passing through the glottis will cause vibration. When this happens a little air escapes pushing the vocal folds apart and as the air flow quickly past the edges of the vocal folds, the folds are brought together again.

• vocal folds tightly closed: the vocal folds can be firmly pressed together so that the air cannot pass between them. When this happens in speech we call it glottal stop.

3 A - Respiration and voicing

The airflow needed for voicing is made by pushing out the air stored in the lungs. This is called egressive pulmonic airstream and is the most common way most sounds in any given language are produced. For a learner to know about this is important because it makes it easier to understand how stress and intonation work.

Once air passes through the vocal track, the next step for making speech sounds is to obstruct the airflow in some way. The first type of obstruction that takes place is done with the vocal folds, which determines whether a sound is voiced or voiceless. At the same time, pressure of the air below the vocal folds varies. There are three main variations:

1) Variations of intensity (high intensity for shouting; low intensity for speaking quietly)

2) Variations of frequency

3) Variations in quality (the result is different types of "voices," like harsh, breath, murmured, etc.)

A solution to this lack of correspondence between what we hear and the symbol we use to transcribe is to use the symbols of the long u and I but without the length mark.

This phoneme has quite a different realization depending on whether it's after and before a vowel sound. When it's before a vowel sound like in clock, life or long the tip of the tongue does touch the roof of the mouth. This is called a clear L. However, when it's after a vowel sound as in still, wheel or animal, the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth much less firmly or not at all. This is called a dark l.

A rather different r sound is found at the beginning of a syllable if it's preceded by a p, t, k. It is then voiceless and fricative. Examples are professional, tree, cross.

Additionally, in BBC pronunciation, when this sound isn't followed by a vowel, it is rather omitted. Examples of this are: car, hard, ever, verse, here, cares.

From the phonetic point of view the articulator of /j/ is practically the same as that of /iː/, but it is very short. In the same way /w/ is similar to /uː/. Phonologically, we say that /j/ and /w/ are regarded as consonants. In order to illustrate this we can show that words beginning with any of these sounds take the article "a" as opposed to the ones that begin with vowels which take "an".

There are some other instances in which a phoneme has two realizations, but they are not interchangeable. In other words, a sound cannot occur in the place of the other. For example, there is a /t/ in the word "tea" and in the word "eat", but in the first case the /t/ is unaspirated, while in the other it is aspirated. In both cases the phoneme is /t/ but they cannot switch around. Therefore we say that these sounds are in complementary distribution.

3 B - Strong and Weak Syllables

Weak syllables differ from strong syllables in that the vowel tends to be shorter and of lower intensity. Some weak syllables don't even have a vowel in its center, and they're called syllabic consonant (ex: bottle). Strong syllables won't have as their peak the vowels schaw, i or u. These are usually found in weak syllables.3 B - The Schwa

Schwa is the most frequently occurring vowel in English. It is associated to weak syllables. Concerning quality, it is a central vowel between half open and half close. Additionally, it is not articulated with much energy. Schwa can occur in initial, medial and final position.3 B - Close front and close back vowels

The close front vowels are i: and ɪ and the close back vowels are u: and ʊ. It is easy to distinguish which one of them occurs in strong syllables, however such distinction not so straightforward in weak syllables. BBC English speakers will find that transcribing the second vowels of words like easy and busy with ɪ doesn't exactly capture the phoneme that they perceive. The same applies in words where ʊ is used in transcriptions although the phoneme in the word has a different quality.A solution to this lack of correspondence between what we hear and the symbol we use to transcribe is to use the symbols of the long u and I but without the length mark.

3 C - English nasals and other consonants - lateral and post alveolar approximant consonants

The basis characteristic of a nasal consonant is that the air escapes through the nose. For this to happen, the soft palate must the lowered. The term 'nasal' refers to the manner of articulation, and there are 3 consonants under this classification: m, n, ng. In terms of place of articulation, these consonants are bilabial, alveolar and velar respectively.3 C - The consonant l

The phoneme l is a lateral approximant. The articulation of this sound is made with the tongue rising towards the roof of the month, which creates an obstruction and makes the air go through the laterals of the tongue.This phoneme has quite a different realization depending on whether it's after and before a vowel sound. When it's before a vowel sound like in clock, life or long the tip of the tongue does touch the roof of the mouth. This is called a clear L. However, when it's after a vowel sound as in still, wheel or animal, the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth much less firmly or not at all. This is called a dark l.

3 C - The consonant r

The phoneme r is a post alveolar approximant. The articulation of this sound is made with the tip of the tongue approaching the alveolar area in a similar motion as if we were pronouncing t or d. However, when articulating r the tongue never actually makes contact with any part of the roof of the mouth.A rather different r sound is found at the beginning of a syllable if it's preceded by a p, t, k. It is then voiceless and fricative. Examples are professional, tree, cross.

Additionally, in BBC pronunciation, when this sound isn't followed by a vowel, it is rather omitted. Examples of this are: car, hard, ever, verse, here, cares.

3 C - Semivowels /j/ and /w/

The sounds /j/ and /w/ are generally called semivowels by many authors. However, some others call them approximates, but what is important to bear in mind is that they are phonetically like vowels and phonologically like consonants.From the phonetic point of view the articulator of /j/ is practically the same as that of /iː/, but it is very short. In the same way /w/ is similar to /uː/. Phonologically, we say that /j/ and /w/ are regarded as consonants. In order to illustrate this we can show that words beginning with any of these sounds take the article "a" as opposed to the ones that begin with vowels which take "an".

4 A - The Phoneme. Complementary distribution and free variation

A phoneme is the smallest unit capable of producing a change in meaning. However, sometimes we can pronounce one phoneme in different ways without changing the meaning. When this is possible we deal with allophones, and the word that has two realizations is said to be in free variation. One example of this is the word "bad", which normally is pronounced with a voiceless /b/, but when pronounced emphatically it is uttered with full voicing and the meaning does not change.There are some other instances in which a phoneme has two realizations, but they are not interchangeable. In other words, a sound cannot occur in the place of the other. For example, there is a /t/ in the word "tea" and in the word "eat", but in the first case the /t/ is unaspirated, while in the other it is aspirated. In both cases the phoneme is /t/ but they cannot switch around. Therefore we say that these sounds are in complementary distribution.

4 A - Symbols and Transcription

4 B - The phonetic value of 's' suffixes

4 C - Plosive consonants. English Plosives.

closure phase: it happens when one articulator is moved against another in order to make a stricture that allows no air to escape.

• hold phase: the articulators remain pressed together, so as the air cannot escape it is compressed.

• release phase: the articulators move apart in order to allow the air to escape

• post-release phase: a sound called plosion can be heard.

For example:

initial position: pop-time-car

medial position: attack-adore-appear

final position: stop-cook-act

4 C - Fortis and Lenis

Some phoneticians argue that the voiceless plosive sounds p, t, k are produced with more force, and therefore receive the name of 'fortis'. On the other hand, the voiced plosive b, d, g are said to be produced with less force; hence they're classified as 'lenis.'5 A - Phonology

s

5 A - Study of the phonemic system

s

5 A - Phoneme sequence and syllable structure

In every language we find that there are restrictions on the sequences of phonemes. For example, no English word begins with the consonant sequence of "zbf" and no word ends with the sequence of a smiling "a" plus an "h". To say more, no word begins with more than three consonants and no word ends with more than five consonants.

The syllable structure has two parts. One is what we call onset and the other is what we call coda. Onset is the sound before the center of the syllable and coda is the sound after it.

If we break down the onset part we will learn concepts like

- Zero onset (if the first syllable begins with a vowel) /ɔːðə/ /aʊə/

- Initial consonants (if the first syllable begins with a consonant)

- Pre-initial (when a word begins with /s/) /spi:k/

- Post-initial (when a word begins with a consonant plus any sound of the set /l-r-w-j/ ) /pleɪ/

As well as for the breakdown of the onset part, we can do the same with the coda part.

- Zero coda (there is no final consonant at the end of the us word: know /nəʊ/)

- Final consonant (when there is a final consonant: stop /stɒp/)

- Pre-final (the final consonant is preceded by another consonant: post /pəʊst/)

- Post-final (It happens when there is a three-consonant cluster and any word of the set /s-z-t-d-θ/ is preceded by two consonants; pre-final and final consonant: helped /helpt/; seventh/sevənθ/)

The English syllable nay have the following maximum phonological structure:

5 A - Suprasegmental Phonology

There are many contrasts between sounds that are not only the results of difference between phonemes. Stress and intonation are also important. For example, if we pronounce the word "import" with a stress in the first syllable we treat that word as a noun but in the case when the stress is put in the second syllable, we deal with a verb. Another way of showing contrast between sounds is by intonation. In the word "right" a raising voice while pronouncing it means that we are inviting our listener to answer or continue with what he or she is saying, but if such word has a falling voice, the word is interpreted as a confirmation.5B - Syllabic consonant

There are some syllables where no vowel is found. When this occurs we find /l-r-m-n-ŋ/ as the center of the syllable.Syllables with the sound /l/ as the center are the most noticeable examples of syllable consonants. For example /bɒtl/ /lisn/ /bætl/ /kʌpl/ .

5C - English fricatives and affricates

Fricatives are consonants with the characteristic the when they are produced, air escapes through s small passage and makes a hissing sound. This sort of consonants are continuant, which means that you can continue making them without interruption as long as you have enough air in the lungs.

There are four voiced sounds /v-ð-z-ʒ/ and five voiceless sounds which are /f-θ-s-ʃ-h/

There are four voiced sounds /v-ð-z-ʒ/ and five voiceless sounds which are /f-θ-s-ʃ-h/

Affricatives are rather complex consonants. They begin as plosives and end as fricatives. There are only two affricatives which are the voiced /dʒ/ and the voiceless /tʃ/.

Now, concerning the classification of the fricative consonants, we say that:

• /f-v/ are labiodental. The lower lip makes contact with the upper teeth.

• /ð-θ/ are dental. The tongue touches the inside of the upper teeth. For example /θʌmb/ /fɑːðə/

• /s-z/ are alveolar. The tongue touches the alveolar ridge, and the air escapes through a narrow passage along the center of the tongue. For example /zɪp/ /sɪp/

• /ʃ-ʒ/ are palato-alveolar. The place of articulation is partly palatal, partly alveolar. The tongue is in contact with an area slightly further back than for /s/. For example /ʃɪp/ /meʒə/

• /h/ is glottal. The friction noise is between the folds. For example /əhed/

6A - The syllable. The nature of the syllable.

The syllable is a very important unit. It plays an important role in setting the rhythm of speech.The syllable may be defined both phonetically and phonologically. Phonetically, syllables are described as consisting of a center with little or no obstruction to the airflow and which sounds are comparatively loud in relation to the beginning and end of the syllable. Syllables can be classified as follows:

1. A minimum syllable (just a vowel)

2. Having an onset

3. Having a coda

4. Having both an onsent and a coda

Looking at them from the phonological point of view involves looking at the diffent possible combination of English phonemes. For example, looking at what can occur in initial or final position. Thus, we learn that words can start with a vowel, one, two or three consonants. Words may end with a vowel or with one, two, three and in some few cases four consonants.