1. The verb to

cast (to throw something forcefully in a specified direction) appearing

in the ST opening sentence "Who cast

the first fateful tomato…" is rendered as:

TT1: lanzó

TT2: lanzó

TT3: tiro

The lexical unit lanzar is much more likely to have an equivalent effect in the target reader than tirar,

because it denotes more strength or violence applied to the action than the

broader and vaguer term tirar, which can also be to

get rid of, to ditch or to dump. Besides lanzó,

another popular equivalent in other translations was arrojó.

2. Determiner that

in “that first fateful tomato”:

TT1:

ese

TT2:

aquel

TT3:

el

The determiner that

is a category-one

type correspondence

because it matches up well with ese.

Both these units express in this case temporal distance. However, in Spanish we

can express further temporal distance with aquel. It is not a mistake per se

because both words convey almost the same meaning (I’m

being a bit picky here), but since that first

fateful tomato was cast over 70 years ago, I

believe aquel does a better job painting a

picture of how that situation developed or how long ago that situation took

place. As far as the TT3 translation el, it represents a word-class shift (from adjective to article), and it

fails to convey the semantic (temporal distance) that aquel or even ese

does.

3. “first fateful tomato”

TT1: fatídico primer tomate

TT2: primigenio y profético

tomate

TT3: primer tomate catastrófico

The TT1 translation is a faithful translation because it stays within the constraints of the ST and expresses the

exact same meaning intended by the author. The TT2 translation is a

free translation

because it focuses on the content rather than on the form.

As far as the TT3 is concerned, the syntactic arrangement

of words, or in more technical terms the immediate

constituents, is misleading to say the least.

The mistake in this translation can be explained citing the structuralist

or taxonimic grammar model.

|

TT1: [fatídico] [[primer]

[tomate]]

|

TT3: [[primer] [tomate]]

[catastrofico]

|

The error in TT3 translation is that it implies that

that tomato was only the first of a series of fateful tomatoes. Much to my surprise, this was a mistake that more than 50% of professional translators committed.

Below are some examples:

·

primer venturoso tomate.

·

primer tomate fatídico.

·

primer tomate preñado de destino.

·

primer tomate crucial.

·

primer trascendental tomate.

4. “a carnival that got

out of hand”

TT1: un

carnaval del cual se perdió el control.

TT2: un festejo

que se volvió incontrolable.

TT3: un carnaval incontrolable.

Krzeszowski speaks about the universal semantic

inputs and the language specific

surface structure outputs his Contrastive Generative Grammar is based on. In other words, he

breaks down into five stages the linguistic process that operates

between the universal semantic inputs, and the language specific outputs. This is, of course, a model

designed to compare languages, but –if we think about

it– it makes a lot of sense for analyzing translations as well.

A few things can be said about the translations

of this phrase in the TT1 and TT2, but all things considered they

both get the job done as far as transferring

the meaning from the source into the target text. That is, they both convey –mind you, in different ways– the idea that the

carnival went from being peaceful, to being a mess. But once again, the TT3 translation has some issues that

keeps it from reaching that equivalent effect status. It makes

it out to be like the carnival was always out of control, and that is

far from what the original text says.

So back to Krzeszowski’s five stages, the TT3 translation only goes past the

three first stages: 1) conceptual input (It’s like

a framework with different slots: agent, patient, time, space); 2) framing the

semantics into categories (like unit, structure, etc.); 3) the syntactic level (minor lexicalizations). However,

the 4th stage concerns inserting dictionary words (major lexicalizations), and TT3 lacks that. It basically lack words like “se volvió,”

“se convirtió,” and what not.

5. “a giant paper maché

puppet parade”

TT1: un desfile

gigante de marionetas de papel maché.

TT2: un desfile

de gigantescos muñecos de papel maché.

TT3: desfile de

marionetas de papel maché.

This leads me to the question: Is the parade giant? Or is it the

maché puppets that actually are? From an immediate constituents analysis point of view, it appear as if the

parade was giant.

However, the TT2 translation as well as almost all of the other

translations from the contest totally missed

this, changed the syntax, and made it look in the Spanish version as if the

puppets were giant. Below are some

examples:

·

“un desfile de títeres gigantescos

hechos en papel maché”

·

“un desfile de enormes muñecos

fabricados con papel maché”

·

“un desfile de muñecos enormes de papel

maché”

·

“un desfile de figuras de gran tamaño

confeccionadas con papel maché”

·

“un desfile de marionetas gigantes de

papel maché”

·

“un desfile de monigotes gigantes de

papel maché”

Having said that, the puppets in La Tomatina festival are indeed

gigantic, so it might be that the error is actually in the source text.

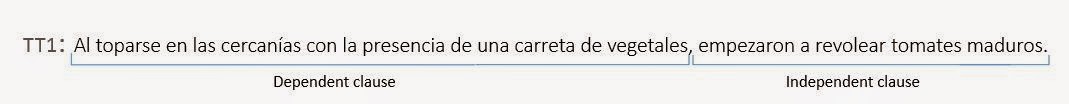

6. “They happened upon a

vegetable cart nearby and started hurling ripe tomatoes.”

TT1: Al toparse

en las cercanías con la presencia de una carreta de vegetales, empezaron a

revolear tomates maduros.

TT2: Se toparon

con una carreta de vegetales que estaba por allí cerca y comenzaron a arrojar

tomates maduros.

TT3: Se

encontraron cerca de un carrito de vegetales y empezaron a tirar tomates

maduros.

Halliday suggests four fundamental categories

of grammar: unit, structure, class and system. He says that these categories are

universal, and that they're sufficient as a basis for the description of any

language. In the category of unit languages are broken down -from

largest to smallest- into ranks, which are sentence, clause, phrase, word and morpheme. The

larger ranks consist of the smaller ranks, and this implies a scale that is

called rank scale.

With that into consideration, Halliday holds

that in traditional linguistics any single sentence will always correspond on a

one-to-one basis with any single

sentence in another language –So was it really

necessary for me to modify the ST sentence so much? In the translation

of the source text sentence, this is a principle that the TT2 and TT3

translators did apply, as you can see in the diagram:

Both these translations correspond on a 1:1

basis the down to the sentence and clause rank with the ST. TT1, however,

disrupts the syntactic features of the original.

While TT2 and TT3 are faithful

translations

because they stay within the grammatical constraints of the ST, TT1 attempts to put more emphasis on

the naturalness than on the syntactic features, regardless of whether or not it

successfully does so.

7. “Innocent onlookers”

TT1:

Espectadores inocentes.

TT2: Los

inocentes espectadores.

TT3: Los inocentes espectadores.

So I’m going to bring up the ignorance hypothesis developed by Newmark and Reibel. It distinguishes an ignorance-without-interference –which is about structures that are not a problem for learners because they will

hardly ever use them– and an interference-without-ignorance, where learners stumble upon the

same errors time and time again even when they

know that a specific grammar structure is not correct

–the can’t help it but to use them. This ignorance hypothesis is generally

a theory used to describe the mistakes one makes in the L2 -however, it can

also be used to explain a mistake done in the L1 due to background

interference

form the L2.

That's why I made a mistake here. In my

translation I omitted the determining article, just like it is done in English. This error is considered to be interference

without ignorance

because no native speaker can be said to be ignorant of the central structures

of their own language –I do know it’s misguided to

omit the article in Spanish, but I did it nonetheless. I paid so much attention

to the source text that I neglected the target text–.

It’s also worth noting that this is an intralingual error and not an interlingual one. Part of the job

CA has in relation to language pedagogy is to predict mistakes –however,

there’s only so much CA can predict that it’s not possible to cover all the

variables. An Intralingual mistake is something CA does not predict.

Quick mention:

|

Also, I wanted to quickly go over this

sentence: "repay the tomato vendors" in which I translated "repay"

as "pagarles." A doubt I had was about whether I should to

put "pagar a los vendedores" or "pagerles a los vendedores."

Most of the other translations used "pagar," but that

sounded a bit odd to me, so I researched and found out "pagarles"

with the object "les" attached to the verb is

optional in some countries, so to say just "pagar" is fine.

TT2 translation said "compensar,"

which I like it as a translation, and the TT3 translation is "reembolsar,"

which I think it's okay as a translation, but my only hang-up is that "reembolsar"

is a transitive verb, so if you say "reembolsar a

los vendedores" it kind makes you think they're gonna put the

vendors into a bag or something like that.

|

|

Then, with clause "locals who defied the law"

I didn't make the same mistake and I put the determining article "los

lugareños que desafiariaron la ley." So did TT2 with the

determiner "algunos" in "algunos veciones que no acataron la ley..."

but I don't like that one because it conveys the idea that they were a few,

but we don't really know about that.

|

|

Also, here, I made a shameful mistake. “Mock”

is translated in both the TT2 and the TT3

as “simulacro.” However, because I got overconfident I thought I

didn’t need the dictionary here. I knew “mock” is “burla” in Spanish, and

to make it fit in the context I translated it as “parodia sobre el funeral del

tomate.” However, little did I know that mock also means “simulacro”.

So I made one of the main mistakes translators have to keep themselves away

from: assuming you know something, and not double-checking. This would be

something like ignorance with interference LOL

|

8. "(it) decided to roll

with the punches "

TT1: optó por

adaptarse al cambio.

TT2: decidió

amoldarse a la situación.

TT3: decidió ser flexible.

In this case we have the idiom roll

with the punches, which literally it’s used in boxing, but figuratively

can be used in any walk of life as well. It

means “to adjust to difficult events as they happen.”

All the three translations do a good job capturing the meaning of the original.

As it is the case with most

idiomatic expressions, they are a category three-type

correspondence.

A category

three-type correspondence is when a language A has a feature that B either lacks or can only be rendered in

terms of B’s, which operates according to different principles. This expression has no direct

translation in Spanish –We can’t find a translation that conveys the same

boxing imaginary–, and therefore an equivalent has to be found. Whatever it is the

equivalent chosen by the translator, it will be rendered as a phrase that

operates according to different principles.

9. “the tomatoes take

the center stage”

TT1: los

tomates toman el protagonismo.

TT2: los

tomates son los protagonistas.

TT3: los tomates toman el centro

del escenario.

The verb

take

as used in the ST sentence is translated as tomar in TT1 and TT3. This word is relatively easy to

learn, so that is why it is safe to say it’s a category-one-type correspondence. At the same time, it is worth

pointing out that even though there is certain correspondence between take

and tomar,

the first has a much higher functional load in English than its equivalent does

in Spanish.

|

The same thing happens with the adjective epic

in epic

paella. We don’t use the word epic anywhere near as much as they

use it in English. An epic paella was translated as una

paella épica in TT3, but in the TT1 it was translated as una

estupenda paella and in the TT2 as una colosal paella.

And another case of the same principle is the

sentence

modifier today.

We could use hoy as a sentence modifier (though hoy en día would be

more common), but we don’t use as often as we would use actualmente o en

la actualidad.

|

|

I wanted to make a quick mention about the

translation of unpalatable tomatoes. I translated it as tomates de mal sabor

and in TT3 it was translated as tomates incomibles. However, I

believe the translation in TT2 which is tomates no aptos para

el consume is fundamentally wrong. A lot of people got confused over

the difference between no comestible and incomible.

|

10. “with the firing of a

water cannon, the main event begins”

TT1: con

el estallido de un cañón de agua, se da comienzo al evento principal.

TT2: con

el disparo de un cañón de agua, comienza el evento principal.

TT3: con el tiro de un cañón

de agua, el evento principal empieza.

Going back to Halliday's suggestion

that any single sentence will always correspond on a one-to-one

basis with any

single sentence in another language, there's in this case a total one-to-one

correspondence on the sentence rank between the ST sentence and the

three TT sentences.

Holliday doesn't specify there has

to be this same correspondence on the level of the phrase unit, but the three

translations begin with the same syntactic configuration: a sentence modifier

adverbial.

The most notable difference between these

translations is than following the adverbial, TT1 makes use of the passive

voice with “se”

while the other two use the active voice. Therefore, it can be said that

there’s not one-to-one correspondence on the phrase rank between the ST sentence and the TT1 sentence.

Because of this syntactic difference, TT1 is a semantic

translation –it

attempts to sound more natural to the TT reader–, and TT1 and TT2 are faithful

translations.

As an aside note, I have seen that among the 20

best translations from the contest, only two of them used the passive

voice while the

other 18 used the active voice. This might be an indicator that

it’s better to use the active voice in this kind of construction.

Moreover, the main distinct feature between TT2 and TT3 is that in one the verb precedes

the subject, and in the other the subject precedes the verb. This marks whether

the translator places more emphasis on the action or on the subject. Again, out

of the 20 best translations, 15 of them chose to put the verb first, and the

other 5 did it the other way around.

|

verb + subject

|

subject + verb

|

|

·

empieza entonces el acontecimiento principal

·

comienza el evento principal

·

marca el comienzo del evento principal

·

empieza la actividad principal

·

inicia el acto principal

|

·

el evento principal comienza

·

El evento principal se inicia

·

el evento principal da inicio

·

El espectáculo principal empieza luego

·

el evento principal inicia

|

No comments:

Post a Comment